Ground-breaking book on dogs in Philippine history

PORTABLE MAGIC

‘Book Haul’ by Cecil Robin Singalaoa, watercolor on cotton rag paper, 2020, 4×6 inches

Photos from the book Dogs in Philippine History

Who’d have thought that the dog, particularly the scrawny and ubiquitous aspin (asong Pinoy) or askal (asong kalye) wandering on nearly every street up and down the archipelago, has a place in our history?

Book author Ian Christopher Alfonso at his UP Baguio lecture

Ian Christopher B. Alfonso’s doorstopper of a tome (654 pages thick), Dogs in Philippine History, restores the dog to its rightful place, complete with myriad photos, some from the US Library of Congress, Smithsonian Institution, Center for Kapampangan Studies of Holy Angel University on a lengthy list of pictorial sources. A historian’s and history buff’s dream book, indeed! It is a research accomplishment that is nothing short of epic.

In a recent lecture at the Museo Kordilyera of the University of the Philippines Baguio, the author regaled the riveted, mostly student, audience with tidbits of information, like did you know that there was a dog, most probably a Jack Russel Terrier, present at Rizal’s execution?

That terrier could’ve belonged to a Spanish official. After Rizal fell upon the volley of shots, the dog circled the body over and over. That was believed to be a bad omen, and it did predict the downfall of Spain, the colonial master.

Then came Bob, the chow chow that Gen. George Dewey most probably found and adopted in Hong Kong en route to the Philippines at the start of the American-Spanish War. When he returned to the US for a hero’s welcome, Bob started a craze for chow chows.

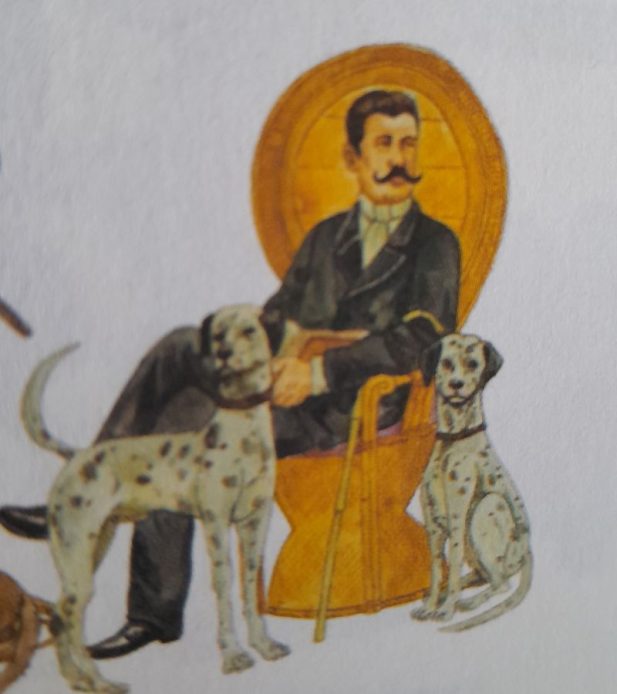

And, Alfonso asked, did you know that the daughter of propagandist Marcelo H. del Pilar owned two Dalmatians? Del Pilar would take them for walks, or would have them present at meetings or by his feet while he was working.

Alfonso said our ancestors did not really like foreign dogs. They considered them lazy and, unlike the aspin, not utilitarian. The forerunners of aspin were useful hunting dogs going after deer or wild boar. These hunters even wore a balata, a collar made from the skin of the hunted animal or in rare instances, it was made of gold. When a beloved dog died, the master wore the balata for a number of days in mourning.

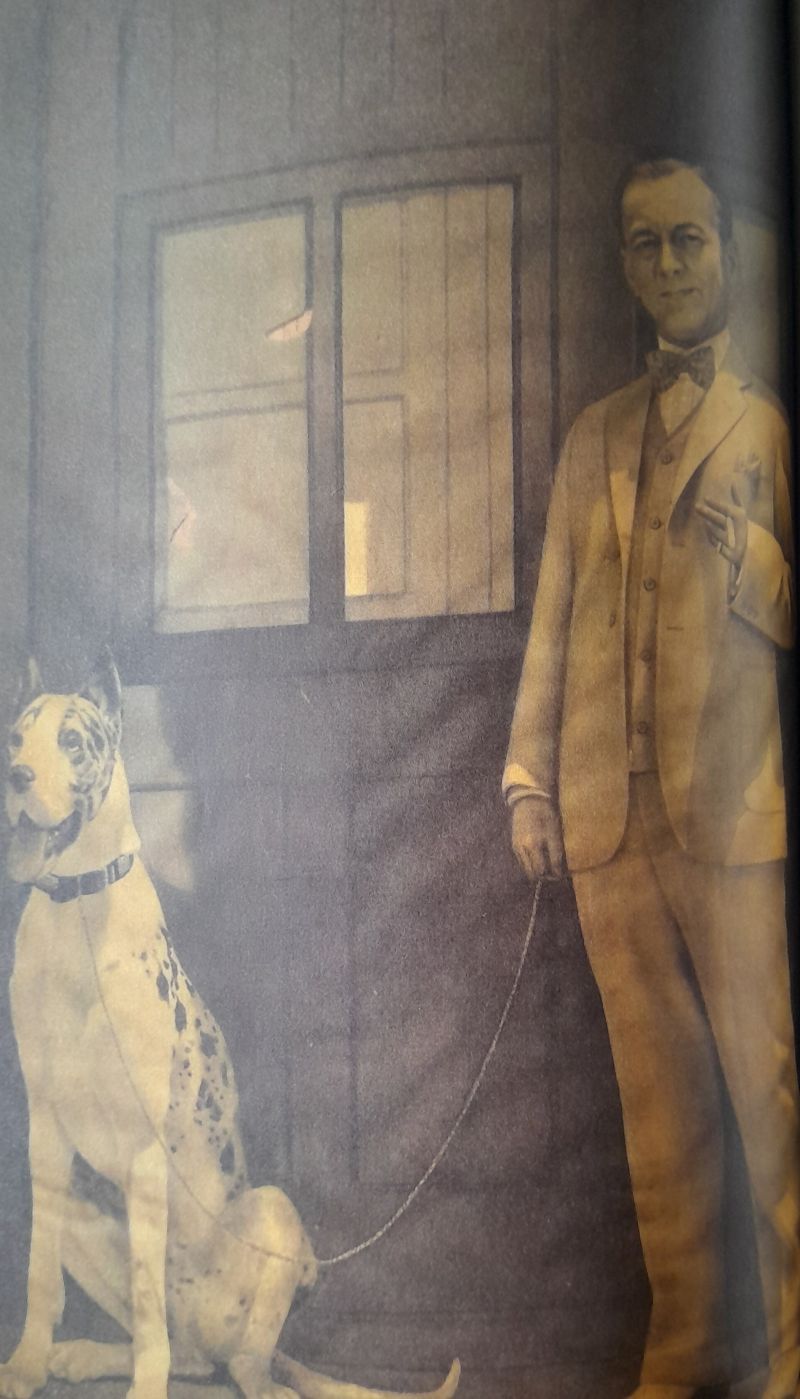

A dapper Manuel L. Quezon with mascot

The author confessed that it was difficult to look for these dogs who were “silent witnesses and participants in our history.” When friends, fellow scholars, and university colleagues learned about his research, they sent him valuable pictures and documents.

Before his book, only veterinarian Enrique Carlos and all-time Filipiniana lover Gilda Cordero Fernando had written about the aspin at any length in a chapter, The Philippine Aso: Life and Hard Times of an Underdog, in the encyclopedia Filipino Heritage: The Making of a Nation (1977). Before that, in 1668, the priest Francisco Alcina wrote the earliest account on dogs and cats in the Philippines. So, there was a huge gap between those two previous works. Alfonso had to start from scratch.

Cordero Fernando described the aso: “25-35 lbs. in weight, short-haired, with a moderately long nose. His common color is tan although he may also be white (which in a Philippine dog is albino), brindle (or tigre) or black. Sometimes he is found with a white streak on the chest and occasionally white stockings.”

She continued, “His ears are erect and point a bit forward. Occasionally the ears may also be floppy. His nose is black. His eyelids are black. His tail is curled into a C. On his forehead he has a very worried set of wrinkles.”

The quotable and observant Cordero Fernando wrote that the characteristics of the aspin are—’matapang, maingay, makuto’

The quotable and observant Cordero Fernando also wrote that the characteristics of the aspin are, in Filipino, matapang, maingay, makuto (brave, noisy, and ridden with lice)!

Alfonso agreed with her on how the aspin had fallen into hard times in the way some people maltreat them by feeding them not just leftovers but even spoiled food. Folklore used to put these aspin in an elevated position since they were immune to distemper, parvovirus, itching and the like.

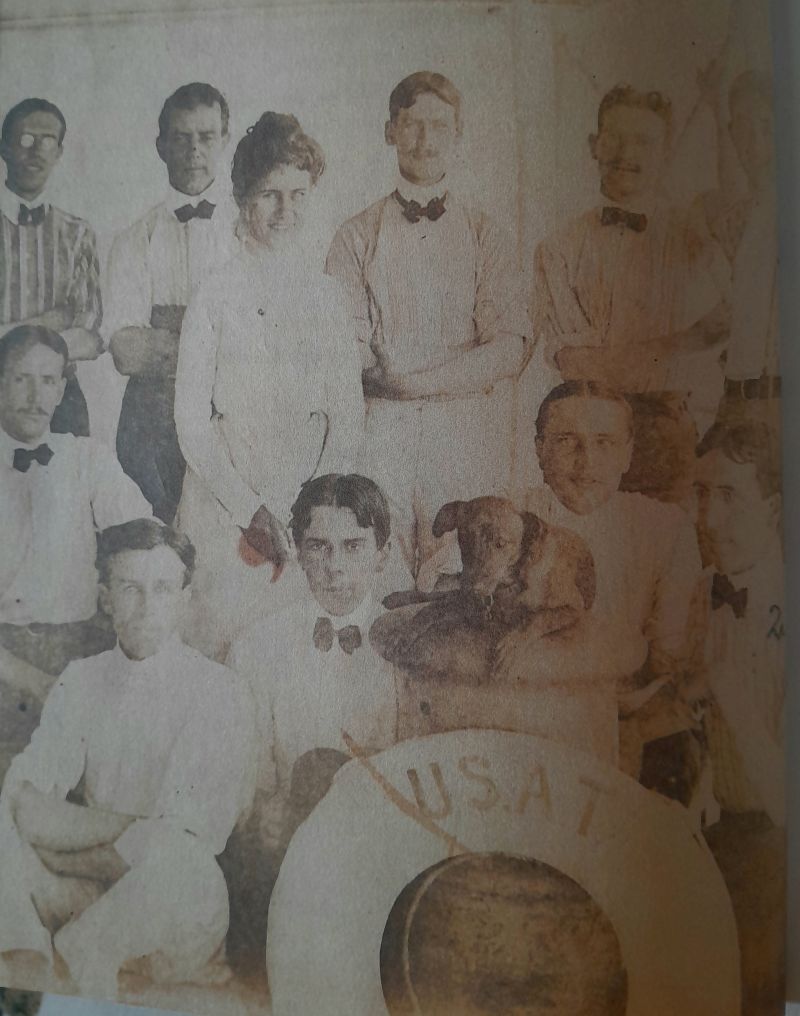

Thomasite teachers with a dog

Even the Panay epic Hinilawod opens with the image of a dog.

Alfonso said sacrifices, like the dao-es, are based on the belief that whoever is ill in the family will be saved when a dog is sacrificed. The dog’s role is: “itatawid yung sakit (the illness will cross over).”

The miraculous image of Our Lady of Peñafrancia is attributed to a sick dog that healed and came alive. Alfonso said, “Even in the highest spirituality, the dog is still there.”

For thousands of years, there was also no rabies in the Philippines. Father Alcina had no recorded case. Alfonso said rabies came with the galleon trade, after other dog breeds were brought into the country. The government’s policy on rabies was to kill the dogs and allow only one dog per family, exempting Spaniards.

Along came Queen Isabella II of Spain who promulgated a more humane protocol concerning suspected rabid dogs (they used to be hammered on the head to slaughter them). Hers was what Alfonso called “a motherly ruling.”

He also quoted a fellow historian about their deep feelings for dogs—it’s called kapwa aso, a brotherly kinship.

Friars with their pets

Alfonso, whose book was 10 years in the making, exhorted students to see the importance of note-taking. “We cannot let the information escape us. I am not a dog whisperer, but there is an infinite lot we can write about the history of dogs, and this can be done with imagination.”