“Squint your eyes and you will see the flocks,” says designer Jude Tiotuico. Suspended from the ceiling is a latticework of abstract birds in flight, their wings seeming to rise and scatter. The design, called The Flock, is crafted from hammered steel with a finish that evokes antique bronze. It is instantly recognizable yet far from ordinary—functional design transformed into sculpture.

“You immediately understand that it’s a lighting fixture,” he adds. “But it looks like art. It’s something that can be experienced and connected with easily, yet is still seen as out of the ordinary.”

The Flock by Jude Tiotuico

Out of the ordinary it is in Subterra: The Untouched Earth, which runs through October 31, at Industria Edition Gallery, The Residences at Greenbelt. The exhibition invites audiences into an imagined realm where natural systems evolve entirely free from human touch.

Featuring five Filipino artists and designers—Jinggoy Buensuceso, Leeroy New, Olivia d’Aboville, Lilianna Manahan, and Tiotuico—Subterra leads viewers beneath the earth’s surface into a vast, speculative terrain that feels both primordial and futuristic. Each contributor offers a vital fragment to this imagined ecosystem, creating a flowing interplay of forms and textures.

Together, they shape a striking visual meditation on how nature might organize and define itself in humanity’s absence.

Subterra is a spin-off from the Philippine exhibit at Révélations, the biennial crafts fair in Paris last May. At the Industria showroom, three pieces from the Paris presentation are displayed by the window.

Jude Tiotuico, founder of Industria metalworks company, created Kaleidoscope, a combination of malleable steel and iridescent polyurethane tree form designed to evoke undulating movement. The piece is covered with Philippine silk butterflies dyed in rurungan by textile designer Olivia d’Aboville. Part of its beauty lies in the shadow it casts on the wall—a shifting play of light and form. “When light hits it at a certain angle, especially in a dark room, the shadow becomes more butterfly-like,” Tiotuico explains.

Fleur by Olivia D’Aboville

The making of D’aboville’s raffia flowers

D’Aboville’s Fleur, a collaboration with Tiotuico’s Industria company, is made of pleated raffia fabric. “I often work with raffia and abaca,” she says. “For Révélations, the challenge was that the Philippine exhibit was in an open space, with no walls and only pedestals. I had to create a three-dimensional piece using textiles. With Industria’s help, we developed a spine—the armature that allowed me to reweave my pleats and form a flower that holds its shape, even though fabric is soft.”

Another featured work in Paris, Hilaw, Laya, is a collaboration between Leeroy New and Hacienda Crafts. Mounted on a log are woven disks that resemble fungi, created by a community for the Negrense furniture and furnishings company.

“We came up with the idea of putting these pieces together as if they existed in a new ecology,” Tiotuico says. “An ecology untouched by humans—that’s why the exhibit is called Subterra.”

Known for his undulating steel sculptures that seem to breathe and ripple with movement, Tiotuico transforms hard metal into forms that feel organic, fluid, and alive.

His Lily Wall Art is a cluster of water lilies made of forged mild steel, softened by the addition of Philippine raffia crafted by d’Aboville. The metal has been hammered into shape, then finished with subtle iridescence—Tiotuico’s signature touch. “We wanted to create giant lily leaves that feel radiant rather than vivid,” he says. “Even though I work with steel, I like to make it appear organic, something that’s about to move.” The piece’s shimmering surface, achieved through a secret finishing process, gives it a sense of depth and motion, while the raffia lends femininity and texture.

Tiotuico’s Lily Wall Art is a cluster of water lilies made of forged mild steel, softened by the addition of Philippine raffia crafted by d’Aboville

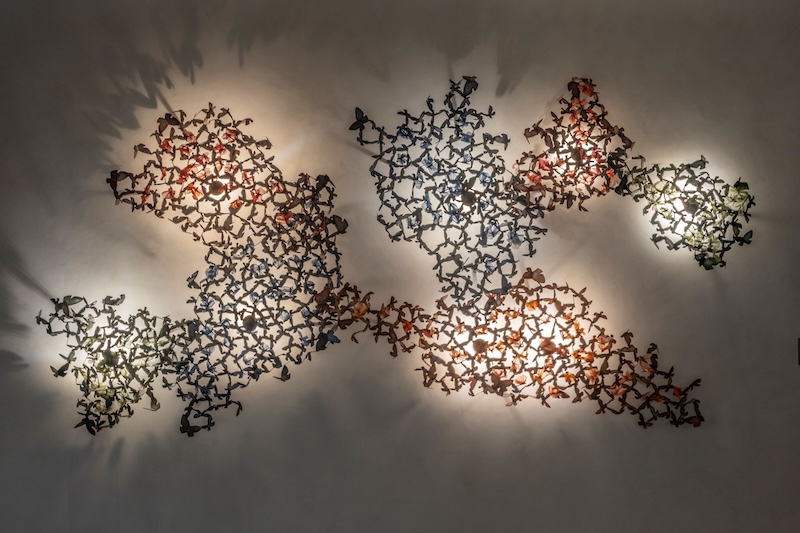

Jude Tiotuico Kaleidoscope 2

Kaleidoscope 2 by Tiotuico

Kaleidoscope 2, another of Tiotuico’s wall sculptures, is a lattice of over a thousand tiny steel branches filled with fabric butterflies. When light strikes it, the work comes alive, casting shadows that deepen the illusion of flight. A smaller tabletop version, Kaleidoscope Bonsai Sculpture, continues this theme of transformation—metal turned delicate, structure turned motion.

Leeroy New

Several of Leeroy New’s works in Subterra feature woven cogon disks created by a community in Cadiz, Negros Occidental. New guided the artisans in developing the forms and color schemes, then stitched the pieces together for his installation. Over time, these disks have evolved into wearable art. The exhibit includes necklaces made from the same materials, and Ina Gaston of Hacienda Crafts has even fashioned a vest out of the woven disks. From this collaboration, Gaston developed its fashion accessories line, “Uma Mi,” which means “our farm” in Bisaya.

New’s Solar Flare is a dense collage of scrap materials from his studio—test molds, resin casts, laser-cut metals—arranged in undulating waves over a wooden base. Embedded among them are fragments of past projects: a flipped Sacred Heart that resembles a fish, a sword piercing its center, a mannequin’s hand touching an orb, and tinted spheres scattered across the surface. “My works often feature organic forms,” New says. “These are like growths—compositions that evolve from leftover materials, reassembled into something new.”

Another piece, The Atlantis, began as a biker’s helmet that New sculpted over with epoxy and fiberglass. The helmet, now transformed into a fantastical object, suggests a cross between a sea creature and a blue flame. “It’s not meant to be worn anymore,” he says with a laugh. “It’s more like a relic or a creature—it lets the viewer imagine their own story.”

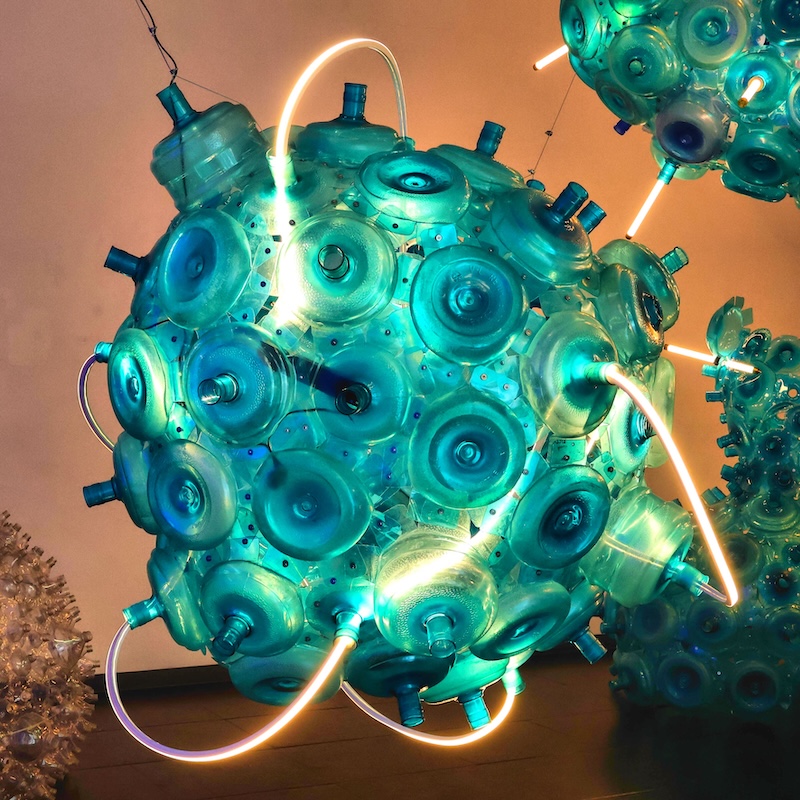

Nimbus by Leeroy New

His lighting installation Nimbus continues this practice of reinvention. Made from five-gallon water containers cut, riveted, and reassembled, the work glows like a translucent cluster of bubbles—industrial waste reborn as ethereal light.

Olivia d’Aboville, a Paris-trained textile designer known for her innovative use of sustainable fibers and handwoven materials, brings a refined sensitivity to Subterra.

Her piece Fleur, a simplified version of the installation she presented at Révélations, features two delicate flowers made of pleated raffia and yellow polyester—the latter forming the warp threads. “I order hundreds of meters a year from Cebu Interlace,” she says. “The owner is a dear friend and was my mentor when I interned there as a textile design student in Paris. For about eight years now, I’ve been collaborating with them, ordering custom fabrics that I use for my textile paintings.”

D’Aboville works primarily with silk, abaca, and raffia, all hand-pleated and dyed to her specifications. “Even though this piece isn’t so big, it uses about 20 meters of fabric,” she explains. “Pleating makes it shrink, but it gives it texture and depth.” For Fleur, she developed a three-dimensional structure that could stand on its own. “The challenge was how to make the work sturdy enough to last,” she says. “Abaca and raffia are incredibly strong fibers—abaca, after all, was once used for ship ropes. Inside the flowers are spines and spokes that hold the pleats in place, giving them volume and permanence.”

Merchickens by Lilianna Manahan

Lilianna Manahan and her paper relief

Lilianna Manahan, best known for her sculptural metal works, turns to ceramics in Subterra with her characteristic sense of play and experimentation. “Ceramics is just a fun material that I can’t let go of,” she says. “Once in a while I go back to it, and I thought making the chicken would be a good way to experiment.”

Her Mechickens series features three-legged porcelain chickens rendered in her signature quirky style. “I work with a porcelain manufacturer, then hand-paint everything after, so each piece is unique,” she explains. The work was inspired by her grandmother’s collection of fantastical animals—a childhood memory reinterpreted in clay. “It’s kind of an ode to my childhood,” she says. “Porcelain fascinates me. It’s delicate but can become anything. Even though it’s been around for hundreds of years, there’s still so much to explore.”

These pieces show that range: one version is covered with drawings inspired by children’s art, while Merchicken #29 is finished in celadon tones with gold accents. “I love the combination of gold and celadon,” she says. “The color comes from the clay itself, not from a glaze. It has a depth that makes it come alive.”

On the wall, Manahan presents paper sculptures from her Notes to the Self Series, where layers of hand-cut paper form dimensional landscapes of emotion and memory. “I started around 2023,” she recalls. “I wanted to illustrate memories and emotions—quiet moments, textures I notice in daily life, like asphalt or clouds, the way they form brushstrokes.” Using different papers, from bamboo to alpaca-based, she combines metallics, blacks, and whites to create tactile meditations on feeling and reflection.

On the wall, Manahan presents paper sculptures from her ‘Notes to the Self Series,’ where layers of hand-cut paper form dimensional landscapes of emotion and memory

In works like Super Clap, shiny and matte textures in black, white, yellow, and blue play off one another in joyful contrast. “I want people to have fun in their rooms,” she says. “We forget to enjoy things as we get older. These pieces are reminders to find joy.” Her layered surfaces—sometimes distressed, with chipping gold leaf and visible brushstrokes—embody that spontaneity. “Those imperfections are surprises,” she says. “They come from how the metal leaf reacts to the glue and how the textures reveal themselves.”

Her Snapshot Series, a burst of color reminiscent of confetti and party favors, continues this celebration of everyday delight. “These are things you forget about when you’re older,” Manahan says. “I mix gouache, oil pastel, and pencil to get that feeling—like when you hear a song and suddenly remember something joyful. That’s what I want to capture in a single frame.”

Jinggoy Buensuceso and Cosmic Flower

Cosmic Flora is Buensuceso’s interpretation of a hallucinogenic flower. “It’s a primal gateway to the unknown, or maybe to a place that’s already familiar,” he says. “I believe in the Subterra. It’s where we begin, and it’s where we return. The flower devours the viewer and brings you to another world.”

The piece is made of powder-coated aluminum, cut by hand “like paper cuttings,” he explains. Each petal is folded and shaped to create soft, curling edges. “It’s not a delicate or nice flower,” he says with a laugh. “It’s a monster flower—one with energy.” A badass flower, perhaps?

His collaboration with Tiotuico is a series of abstract metal logs can be used as a table. “The logs represent the full cycle of life,” Buensuceso says. “Death, decay, and renewal. After you die, you decay and offer yourself to the earth. Then life begins again.”

He recounts seeing a massive metal log at Tiotuico’s factory. “It had been lying there for a long time,” he says. “I told Jude, let me rework your piece. I had this concept of death, decay, and beginnings. I called it The Offering.”

Made of molten brass and oxidized metal, The Offering captures both decay and growth. “The molten brass represents the growth of trees,” he says. “When the tree dies and decays, it gives rise to new life—like mushrooms sprouting from fallen wood.”

Functional yet deeply symbolic, the sculptural furniture carries Buensuceso’s signature style: organic, raw, and designed for connection. “It should always be functional,” he says. “You can sit on it, rest your drink on the coasters—it’s made to be used, not just admired.”

Asked if their work crosses the line between art and decoration, three of the four designers offer thoughtful, often overlapping views.

D’Aboville says she occupies the space between art, design, and craftsmanship. “There’s a very fine line,” she says. “I have one foot in all three. Technically I’m a textile designer. I studied applied arts, not fine arts, but I use those techniques to make one-of-a-kind pieces. In that sense, they can be viewed as art.” Her work is minimal and often monochrome; she used to favor earthy tones and ocean blues, but after having children she began to introduce more color. “Color felt bold at first, but now my work is more vibrant and playful. It really depends on the viewer—how they see it and what they feel.”

When raffia flowers meet the metallic Cosmic Flower

Buensuceso frames his practice as hybrid by design. “I don’t call my work decorative,” he says. “I’m part of the hybrid movement—blurring the line between art and design. If you’re purely an artist or purely a designer, it’s hard to move between worlds. But as a hybrid, it’s natural to create functional art. Objects tell deeper stories.” Buensuceso describes his pieces as cosmic and existential: “Jude is the tierra, the earth. I’m cosmic and beyond. My work engages questions of existence—why we are here—and each creation offers a hint or an answer.”

Manahan treats the distinction as open-ended. “Art can be decorative, and decorative things can be art. If it makes you happy or triggers emotion, it’s doing its job. If it makes your place look nice, that’s fine too,” she says. Her process bridges disciplines; her background in product design and paper modeling informs the structural approach, while paint and surface treatment bring a fine art sensibility. “The modeling and the paint are part of one creative process,” she explains.

Tiotuico approaches the question from a designer’s point of view. “We all come from a designer’s DNA, so we start from a point of connection. For me, art is when you create to be understood; design is when you understand before you create.” He adds, “We think about connection with humanity. I build for people so they can understand and connect with what I make. Whether a piece ends up in a home or a gallery, someone should be able to get it at a glance.”

Mutya Buensuceso and Milo Naval

Guest Kenneth Cobonpue designs this elephant rendered by Industria