That The Legend of the Condor Heroes: The Gallant quietly slipped into Netflix’s catalogue is something to be happy about. It’s not an insipid action movie and would have been read from cover to cover if it were a thriller novel. It was China’s fourth biggest film for 2025, “grossing US$35.6M including US$1.5M for Imax (deadline.com).”

The movie is based on chapters 34 to 40 of wuxia novel The Legend of the Condor Heroes by Jin Yong, which centers on Guo Jing’s transformation from martial artist into an empire’s savior and guardian.

Actor-singer Xiao Zhan as Guo Jing is one reason to watch. Zhan’s a master in portraying characters in costume dramas, i.e., dark arts cultivator Wei Wuxian in The Untamed, exiled crown prince and mystical arts cultivator Shi Ying in The Longest Promise, and royal minister Zang Hai in The Legend of Zang Hai.

Another reason is Hong Kong director Tsui Hark, who’s been criticized for making a lackluster film and digressing from the original wuxia storyline. The criticism is unjust because Hark kept to the wuxia structure of conflicted loyalties, heroes and villains, hidden identities, and love, complemented by his signature fast-paced editing and wire-fu choreography. (Wire-fu is the combination of traditional kung-fu and wirework, which is a cinematic hallmark of Hong Kong action films. The word is a portmanteau of wire and kung-fu.)

True to form, Hark kicked the action into high gear early into the movie with scenes of elderly masters vaulting over rooftops and overcoming the enemy with waves of water, and Guo Jing running up a vertical pole, backflipping, and controlling the wind’s direction to disperse the lethal gas in the atmosphere.

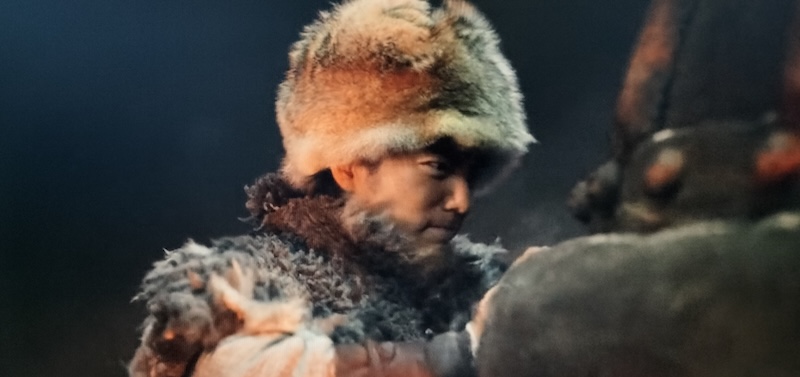

Guo Jing, Song dynasty’s formidable martial arts warrior (Screengrab from Netflix)

Guo Jing entered the screen crouching on the edge of the cliff observing the Mongolian soldiers galloping below. He’d just hung a small pinwheel on a branch for Huang Rong (Sabrina Zhuang) to find him. In a flash, the soldiers were on the cliff and interrogating him. Why was he there? Why did he speak in fluent Mongol when he didn’t look Mongolian? At this point, Hark kept to the wuxia novel’s backstory of Guo Jing. With the death of his father, Guo Xiaotian, his pregnant mother Li Ping somehow ended up in Khan’s camp, and Khan raised Guo Jing as his own son.

Genghis Khan, Guo Jing’s warmhearted adoptive father (Screengrab from Netflix)

The digression came with wuxia Genghis Khan from the historical Genghis Khan who, per history.com, destroyed civilizations. Tellingly, Hark skirted Khan’s being responsible for the deaths of 40 million people, with the Middle Ages’ censuses showing China’s population plummeting by tens of millions during his lifetime and the Mongol’s attack possibly reducing the entire world population by as much as 11 percent (history.com).

Hark transformed history’s brutal conqueror into a compassionate surrogate father, who walked away when Guo Jing declared he’d fight him to defend his home. This new characterization enabled Hark to segue easily into Guo Jing and Huang Rong’s romance, enlivening it with a rivalry between Princess Huajun, Khan’s daughter and Guo Jing’s betrothed since birth, and Huang Rong, the 19th chief of the Beggars’ Guild.

Putting his own spin on the theme of unrequited love, Hark clipped the women’s budding friendship with Huajun discovering Huang Rong’s real identity, and then staged the clichéd catfight between the two into a duel to the death without the stereotypical histrionics. They were women, yes, but warriors, too. The adversaries gracefully danced and leaped as they parried and attacked with their weapons of choice—Huang Rong with her bamboo staff and Haujun her saber. Huajun vented her feelings of abandonment and hurt on Guo Jing finding someone, while Huang Rong defended herself from the wrath of a rejected lover.

Xiao Zhan as Guo Jing and Sabrina Zhuang as Huang Rong challenging the Mongol army (Screengrab from Netflix)

Love in the era of a benevolent Genghis Khan is depicted in various ways. Veering from the saccharine romance tropes of Korean and Chinese dramas, this film presented romantic love in Guo Jing and Huang Rong’s search for one another during their separation, Huang Rong’s gaze at Guo Jing demonstrating his new martial arts skills before the Mongol camp, and Guo Jing’s affirmation of his love for Huang Rong.

Guo Jing was an awkward nerd vis-à-vis love, but he didn’t hold back. His words to Huang Rong were straightforward: “Whatever trials lie ahead, I shall protect you.” The pinwheels and carved Mongol word meneg (fool) on a rock—the tail of the character told her his onward direction—that he left her were “letters” of love and reconciliation, after he realized his mistake of abruptly cutting ties with her after he wrongly accused her father of murder.

His words to Huajun were equally unambiguous. He told her he couldn’t marry her because he met someone he’d search for “to the brink of the world,” and that his feelings weren’t “just fondness. (They were) beyond that…I have no idea what it felt to like someone.”

In the same manner, Huang Rong was frank as well as mature. In one touching scene, she, misunderstanding Guo Jing’s situation, left Khan’s camp so as not to impede his betrothal to Huajun.

Filial love was underscored through Guo Jing’s relationships with his adoptive family. Guo Jing and Khan received each other warmly after a long time apart. Guo Jing was Huajun’s annoyed elder brother when she rushed into his tent and hugged him. Guo Jing and Tolui’s closeness was apparent, with Guo Jing rescuing Tolui and his troops from being beheaded. Conversely, Tolui pleaded with their father to not execute Guo Jing for his refusal to lead the Mongol troops against the Song empire. As a beneficent leader, Khan relented and commuted the sentence to house arrest. And Tolui accepted Guo Jing’s decision to leave his Mongol family for good.

Motherly love was personified by Li Ping, who waited for two years for Guo Jing’s return. He travelled to the Middle Land to learn martial arts from the Seven Freaks of Jianghan. Along the way, he met Huang Rong, who introduced him instead to two powerful masters of Middle Land martial arts and learned the techniques of 18 Dragon Palm and harnessing his internal force.

When Li Ping learned that her son had fallen on Khan’s bad side, she gave him his father’s cloak, a symbolic passing down of legacy. She advised him to live a life without regret and to stay true to his principles and heritage. What followed was the most tragic scene in the film: Li Ping killed herself to spare him the agony of deciding whether to protect her or save their hometown.

Patriotic love was effortlessly woven into the story with Guo Jing heading to his hometown to help repel the Mongols’ impending attack.

The over-the-top martial arts sequences are the film’s massive allure

A massive allure of the film is the over-the-top martial arts sequences that are reminiscent of Stephen Chow’s Kung-fu Hustle, except they’re not farcical. Wire-fu choreography and altruistic heroes preventing an Armageddon are the stuff that Asian action films are made of. The action never lets up like in Western cowboy films, but comes out better.

Guo Jing against Venom West’s men (Screengrab from Netflix)

The first time Guo Jing and Venom West, another powerful master of Middle Land martial arts, came to blows with the latter pinning down Guo Jing under a colossal dome, Guo Jing escaped by striking the dome with his hands. Their second jaw-dropping brawl was when Venom West had transformed into a demonic warrior after mastering a fake version of the coveted martial arts book Novem Scripture (or Nine Yin Manual). It was like a grand battle between Luke Skywalker (the Force) and Darth Vader (the dark force).

Guo Jing saves himself from being crushed by a dome. (Screengrab from Netflix)

Another epic scene was Guo Jing demonstrating his control of fire. He did several rotating midair flips before letting loose fireballs at the towers of mountain-high firewood.

Part and parcel of the fight scenes were the amusingly quirky names of the fighting techniques that, Gua Jin learned, his masters recited with gravitas, i.e., The Dragon Soar, The Dragon Quake, Two Dragons Fetch Water, Dragon in the Field.

Refreshingly, Huang Rong and her followers were unwitting comedians, staying the possibility of ennui with the fight scenes. In one scene, Huang Rong was standing outside the tent, listening in on Guo Jing and her bumbling followers discuss the book on war strategies. To help, she sketched the strategies and passed them through a hole in the tent. In another, her followers, clueless of Huang Rong and Guo Jing’s romance, openly told her that Guo Jing and Huajun made a beautiful couple.

One didn’t have to be well versed in the wuxia novel to enjoy the film. In fact, it’s a plus factor in the film’s success. Hark presented his intriguing take on Genghis Khan and didn’t dilute the crux of wuxia, which would have resulted in a less fantastical main character. In Hark’s direction, Guo Jing still came out as a legendary martial arts warrior.