I never thought lightning would strike twice in a couple of years.

As I write this, it’s been a month since another family tragedy struck.

As the country observed Andres Bonifacio Day last November 30, I got curious about a news item on another reported encounter between military and rebel groups in Barangay Kamansi, Kabankalan, Negros Occidental. I immediately sounded off my media friends in Bacolod.

In another Facebook post on the same day, we learned that my son-in-law, Ericson Acosta, and his companion were arrested on the same day at about 2 in the morning.

I immediately asked my grandson to sound off his maternal grandmother, 90-year-old Liwayway Acosta. I took it lightly and hoped, if worse came to worst, that my grandson and I would still get to visit Ericson in a detention hall.

But before noon of the same day, November 30, a friend confirmed another death in the family. He wasn’t detained after arrest. A witness claimed that he was made to walk around the house where he was arrested, then was allegedly struck down.

Meanwhile, the local media ran a military account of an alleged “encounter” with “rebels.”

After Ericson’s death was confirmed, I stared at my computer and let out a howl of grief.

I was thinking of only my grandson Emmanuel who has been orphaned twice in just two years. He was with his University of the Philippines (UP) friends observing Bonifacio Day in Mendiola, when he got wind of the news ahead of me and his maternal grandma.

Somebody described how he saw my grandson pause, apparently stunned by the news, and quietly walk to a street corner and cry. I never saw him cry when his mother died.

This was a repeat scenario: on the day we heard the news, we had to book a flight to Bacolod, and to work on assorted permits before we could claim the body in a Kabankalan funeral parlor.

It is a two-hour ride to Kabankalan from Bacolod on an early morning. First, we had to get an incident report from Barangay Camansi. The barangay head didn’t want to sign the incident report, but with gentle prodding from our lawyers, he did sign, but not before he made us aware that he was king of his turf.

My grandson knew the routine would be similar to when he claimed his mother’s body a year ago in a Silay funeral parlor. We needed not just a barangay clearance but also police clearance, health clearance, city hall clearance, and once done, we needed an embalmer’s signature to confirm the existence of the body. We spent a whole day doing that, running around various offices and getting derailed by the absence of officers who were out attending seminars.

My grandson knew the routine would be similar to when he claimed his mother’s body a year ago in a Silay funeral parlor

A doctor was available to sign the health clearance only on December 12. We could not wait that long, and it was only December 1 when we arrived. We decided that we would transport the body to Manila and have it cremated later.

The funeral parlor, on the outskirts of Kabankalan, was surrounded by men in uniform the day we went. We learned later that the owner was a traffic enforcer and a Christian pastor on the side.

This was the moment I feared: when my grandson would see his father’s lifeless body in a roomful of dead people.

Three years back, right before Christmas, he had a few days with his parents in Bacolod. Just after my last concert at the Nelly Garden in Iloilo City in 2019, I met my grandson in an inn and gave him a room and breakfast before he headed to Bacolod on a ferry boat.

A younger Emmanuel Acosta with parents during happier times. (Photo from Efren Ricalde)

That was the last time my grandson saw his parents alive.

Past reunions with his father included frequent visits to a Calbayog jail in 2012-2013.

When we finally saw the body of Ericson, I couldn’t help looking at my grandson. I have never seen that face so devastated.

When his mother died, he took it all calmly. Or so I thought.

Seeing him before his father’s body, I thought I couldn’t bear the sight. I took a quick look at my grandson’s face and saw loneliness of a devastating kind.

I retrieved the clothes of his father from the funeral parlor embalmer, after which we headed back to Bacolod fast to get another permit to bring the body back to Manila.

“You want to see Tatay’s body before we bring him to the airline’s cargo office? We bought him new clothes,” said my grandson. “No,” I said. “I will see him in Manila anyway. Let’s just have a quick dinner.”

We realized we had missed our Friday lunch, busy as we were getting all those required permits. My grandson and his ninang flew ahead to Manila with his father’s body to arrange for cremation. We followed later on the afternoon flight.

Back in Manila, we prepared for a Requiem Mass before cremation. My grandson received a metal rose from a mother whose daughter had been incarcerated also for years. Then grandson and I watched Ericson’s body as it was brought to the hot furnace.

When we finally saw the body of Ericson, I couldn’t help looking at my grandson. I have never seen that face so devastated

I realized my grandson and I had been witness to the cremations of his parents the past two years.

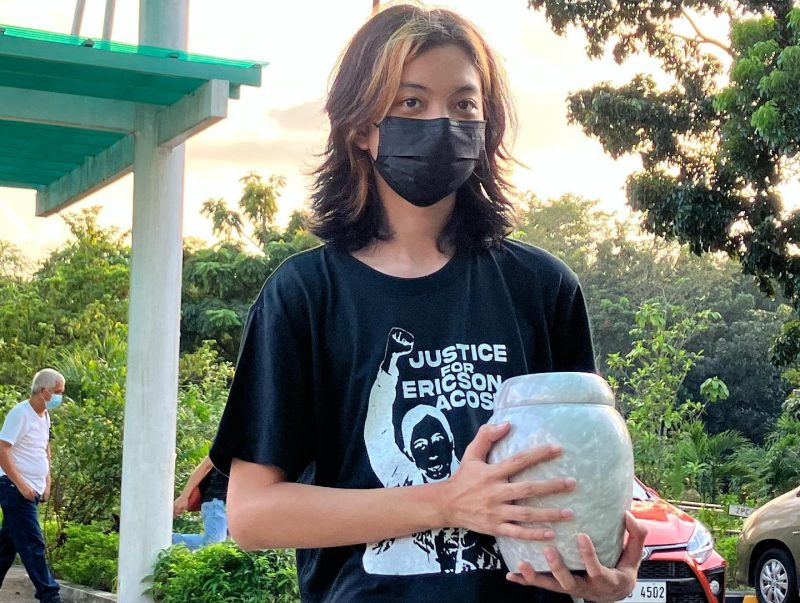

Emman Acosta with his father’s urn. (Contributed photo)

There was a two-day tribute to Ericson before his internment in the Pasig cemetery. Bibeth Orteza intoned in her tribute to Ericson: “Was it coincidental that National Artist for Film Lino Brocka was also paid tribute to in the same Gumersindo Garcia Hall where poet Acosta is being honored now? Was it coincidental that Ericson died on the day the country was commemorating the birth of Andres Bonifacio?”

Others who offered songs and poetry during the four-hour tribute were flutist Jay Gomez and pianist Katherine Asis, Dong Abay, Jess Santiago, Renato Reyes, Jr., the Patatag group and many others.

In the final tribute to his father at the Gumersindo Garcia Hall of UP Diliman, my grandson had come to terms with another death in the family.

On a lighter note, he spoke candidly of his father as musician: “I am my father’s worst critic. I am always critical of everything he does. I notice he plays the guitar with just one chord. So I called him The One-Chord Wonder.” There was laughter from the audience.

Then his final remarks, which went viral on the internet and reached more than 5 million netizens: “I have nothing against my parents for spending more time with the poor and the oppressed than with me. I believed in what they fought for. There is no rancor in my heart that my parents have other families—the masses. That was made clear to me by Tatay and Nanay. When they were heartlessly killed, the more I believed in their cause.”

I have nothing against my parents for spending more time with the poor and the oppressed than with me’

On the day Ericson joined my daughter Kerima in the grave, I could only react with another poem.

We are done

With grieving

And wiping away

Persistent grief

Like my grandson

Who let it all fall

Where it should

On a street corner

Where his parents used to tread

Along the hollowed street of Mendiola

What were those tears for?

He expected to reunite

With dear father

In a detention cell

And perhaps make music

Together

For the last time

The next thing he knew

His father was arrested

In the hinterlands of Kabankalan

Then made to do a few turns

With his companion

Only to meet their imminent death

In a sudden rain of bullets

And bolos tearing away

At their skin

Months back

I always requested

Massenet’s Meditation

To remember

My late daughter

Now it is time

For that soulful music

To remember his father

I always ask my grandson

To sit with me in rehearsals

While Massenet’s Meditation

Floats eerily

In the auditorium

Surely

Music has a way with grief

Perhaps it is a good way

To confront death

Perhaps the gentle way?

Now tell me

How should music metamorphose

Into balm

For our weary spirit?

Perhaps music

Can guide us

Into the periphery of acceptance

Even if the labyrinth

Is oozing

With excruciating pain

I did carry that urn

With his mother a year ago

Now I am torn with grief

Seeing him

Carrying his father’s ashes.

Is it

Time to move on

And fly on the wings

Of song

And remembrance?

Last photo of the author’s family with Ericson and Kerima and her sisters Tamara Irika and Karenina and niece Tanya, Litz Tariman.