At work in his studio in 2016

Photo by J.L. Javier

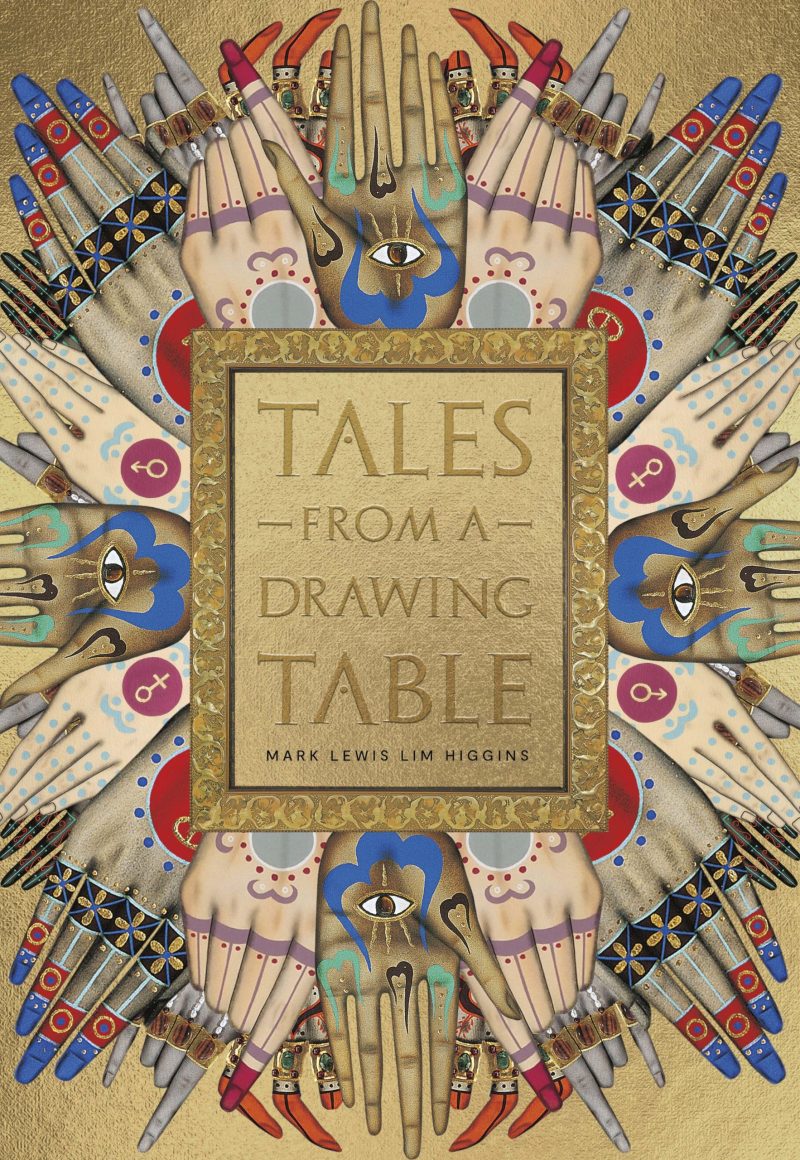

Cover of ‘Tales From a Drawing Table’

Curiouser and curiouser

There is a lot to frighten a postcolonial critic about Mark Higgins’ book on his art. But this critic yields to pleasure. Instead. This is a most curious turn.

To be sure, the book’s pleasures are neither seductive nor giddy. At least not in the usual ways. It is a gentle read, notwithstanding its visual immoderation. The book is a massive piece of jewelry with multi-faceted gems.

Salvacion Lim Higgins at her work desk, Mark Higgins at his

Mark Higgins—himself a gentle soul, however given to multiply-faceted richness—made a book that pulls off something remarkable.

It is a true art book. Not a book about art but a book that proposes to be art. Not a book with texts and pictures of his artwork, although yes it is a catalogue raisonné in one sense. In another, overlapped sense, it is an autobiography. But anyone who has tried to lift it (heavy, heavy tome) physically understands that the book is itself: an object.

-

Dioskouroi (2004)

Gouache, acrylic, chalk pastel, 23.5ct gold leaf and semi-precious stones and gems.

-

Semiramis (1999)

Gouache, chalk pastel, 23.5ct. gold leaf, and variegated metal leaf on paper.

-

Rashaida (2002)

Gouache, chalk pastel, acrylic, 23.5ct gold leaf, semi-precious stones and gems.

-

Amalric (2003)

Gouache, chalk pastel, acrylic, 23.5ct gold leaf, semi-precious stones and gems.

Inscrutably occupying space, it stays with the eye. It has the presence of a straightforward sculpture, a rectangular block of something rather than a compilation of thin leaves. Tales from a Drawing Table rests on any surface the way a finial or crest rests calmly atop a cabinet. It does not necessarily speak.

But it does invite exploration: a die-cut rectangular hole on its hard slip-on case gives the book title a frame and a doorway. Inside the book, readers will remember this portal, which might seem to have commenced flight into the intricately-articulated ceilings of the Alhambra, or to the tiny universes inside Persian miniatures, or Samarkand’s iridescent mosaics.

And yet Mark quickly disabuses the reader: the book is not about any of these places—that he did nevertheless transit, picking up visual and tactile ideas like shiny things on the road.

His book repetitively does this twist. Wherever it begins to feel like an extravagant travelogue, the book doubles back: the pictures of places are mere signposts in an imaginary. They are not enticements to destinations. The imaginary does not stay with any location.

-

Samudra (2017)

Gouache, chalk pastel, acrylic, 23.5ct. gold leaf, and Japanese tinted silver leaf on paper.

-

Devata (2017)

Gouache, acrylic, chalk pastel, and 23.5ct gold and metallic leaf on paper.

-

Hiram (1999)

Gouache, chalk pastel, 23.5ct. gold leaf, and Japanese tinted silver leaf on paper.

-

Suleiyman (1999)

Gouache, chalk pastel, 23.5ct. gold leaf, and Japanese tinted silver leaf on paper.

Gliding, not plunging

Tales from a Drawing Table is the whole thing, no matter what, how astonishing the detail. I encourage Mark’s reader to resist getting lost in the fantastic: the obscure calligraphies, images of gemstone-encrusted framing devices, rare papers, and lots of opulent cloth. Brocaded, ikatted, twilled, embroidered, imprinted, and adhered to gilded surfaces—the textiles are made to produce multiple optical planes, and suggest universes-in-universes.

But it is important to stay with the experience of gliding above, not plunging into minutiae.

To create the book, the essential artmaking technique was a kind of collage, in this case executed as flat, printed pages—rather, flat, printed spreads, because the visual units are indeed two juxtaposed images on two adjacent pages. Typically across the book, a page shows an awesome location and is paired with the facing page showing Mark’s artwork.

There is no meaning delivered but one: that art is a magician’s performance

Texts by Mark and other authors break the juxtapositions but continue the pull into the surfaces that all seem calligraphic. That is, everything seems to deliver meaning. In due course, while leafing slowly through the book, there is no meaning delivered but one: that art is a magician’s performance.

Khotan (2005)

Gouache, acrylic, chalk pastel, 23.5ct gold leaf and semi-precious stones and gems.

Angkatan (2015)

Gouache, chalk pastel, and 23.5ct gold and metallic leaf on charcoal paper and Chinese silk.

The calligraphies actually do not speak. Gliding across the illusions of textural and sculptural inner chambers—it becomes clear that the book’s and the artworks’ depths are Marks’ alone. The reader and the lover of his encrusted paintings enjoy the pleasures of the glide.

Flashes of ancient Central Asia and Africa are pictorial thresholds into Mark’s imagination and clues into his biography. The critic might balk at the exuberant Orientalisms. But Mark is a Filipino who is not self-orientalizing. His flashes of visual insight—travel to and from out of a metaphoric hermitage strangely amid Manila’s fashionable set—are not acquisitive.

Rather, “they” possess him—the places, gold and black leaf, the bodhisattvas of all religions, the fastidiously wrought frames, on and on. And so, unlike Orientalists who are actors in colonial projects, Mark is the landscape possessed, and made fecund.

An archaeology (apologies to Foucault)

All of which leads to the portraits at the centers of the encrustations. They have variously colored skins but the same thin, incision-like eyes. Some are him. There are others. Part of the magic is that each might be seen as self-portraits. Each Mark looks at you.

He is not the object of a viewer’s gaze. He is the person looking.

That Mark is a child of the fashion industry may account for his possession by meaningfully textured things and places. (I won’t tell you whom his mother is, if you don’t know yet.) But I would like to insist that he had also escaped the industry, which does not lend itself to meditative states. Mark picked up the shimmers of origins and travels: where the cloths, gems, leaf, fibers, engravings, patterns, beads came and moved; and from where and through what routes he was transported into mindscapes distant from any current vogue.

What the book lays out to the reader is hence him, although only via intimations about his imagination. The book accomplishes a tender contradiction. The aesthete as magician can only stun, without revealing inner workings.

We were delighted to discover that we love one book in ways people don’t love books

When I first met him, recently, we were delighted to discover that we love one book in ways people don’t love books. The Dictionary of the Khazars, by the Serbian writer Milorad Pavicć, is written as a lexicon of a language of an obscure Caucasian people. We know that incomprehensible books are typically unloved.

There is an edition for women and an edition for men. One will kill the reader upon opening.

It is all fabulation. Nonetheless it is true indeed that about a millennium ago, the Khazars had something to do with the founding of Kyiv, focus of enormous global attention right now. And while I normally do not consult Wikipedia, I did quick look-see to recall the ways the Khazars flutter between real and improbable. This paragraph made me laugh:

“Chronicles of the time are unclear on Khazar’s linguistic affiliation. The tenth century Al-Istakhri wrote two conflicting notices: ‘the language of the Khazars is different than the language of the Turks and the Persians, nor does a tongue of (any) group of humanity have anything in common with it, and the language of the Bulgars is like the language of the Khazars but the Burtas have another language.’ Al-Istakhri mentioned that population of Darband spoke Khazar along with other languages of their mountains. Al-Masudi (896 – 956) listed Khazars among types of the Turks, and noted they are called Sabir in Turkic and Xazar in Persian. Al-Biruni (973 – 1050), while discussing the Volga Bulgars and Sawars (Sabirs), noted their language was a ‘mixture of Turkic and Khazar.’ Al-Muqaddasi (c. 945/946 – 991) described the Khazar language as ‘very incomprehensible.’ Ibn Hawqal, who travelled during the years 943 to 969 AD,wrote that ‘the Bulgar language resembles that of the Khazars’.

I indulge. I include this extended quote here because Mark’s imagination is similarly populated by things and thoughts that together resist classification and defy rendering into language. And if it is a challenge to mirror in text, then it is terribly difficult to think it to be Contemporary Art.

On the other hand, his paintings that look like fervid reconstructions of the Mother of Perpetual Help icons—flat portraits surrounded by storied materials traded across Eurasia for centuries—can only be produced by a contemporary mind, supported by a heart at peace.

Mark’s book further flattens his ouevre: the pearls and locations and stuff are fixed in the single dimension of the printed page. In this flattening, Tales from a Drawing Table is an archaeological site in a compact box. Like archaeology’s layers, the pages are each a concatenation of inventions and traces of lives.

Its readers will, I believe, discern, not just Mark’s fulsome capture of his life lived thus far and imagination in full flight—but the reader’s own archaeology of self.

Mark aged 30, when his book begins.

Photographed in the Forbidden City, Beijing.

(Editor’s note: Mark Lewis Lim Higgins was born in the Philippines to parents Hubert Lewis Higgins and National Artist Salvacion Lim Higgins. He was educated at the International School Manila, and eventually studied fine art in Toronto and fashion design at Parson’s School of Design in New York. In the succeeding years, he would spend several months at a time painting in Rome, then between New York and Hong Kong mounting his exhibitions. He has done two solo exhibits in the Philippines—the first in 2007 and the second in 2019, both at Ayala Museum.

In the past 12 years, Mark has served as director of Slim’s Fashion & Arts School, founded by his mother in 1960. He is the co-author of two previous books, SLIM: Salvacion Lim Higgins – Philippine Haute Couture 1947 to 1990, published in 2009, and Fashionable Filipinas: An Evolution of the Philippine National Dress in Photographs 1860-1960 published in 2015. He is about to launch his third book—a complete collection of his body of work over the past thirty years, entitled Tales from a Drawing Table—in the forthcoming Art Fair.)